Hello and happy Friday!

Jupiter 2024: Very soon there will be details on this year’s in-person writing retreat!! I am super excited about this and can’t wait to tell you more.

In the meantime, check out the podcast Writing in the Dark, a series of cozy conversations with my Jupiter co-leader, Ralph Walker. We just got some amazing new cover art—thanks to everyone who weighed in!

I am about to announce the details of a very cool new storytelling project. Stay tuned!

In the last couple of months, I have gotten pretty obsessed with jigsaw puzzles. It started idly for me, a simple winter pastime. But it’s so much like writing that I’ve become pretty obsessed.

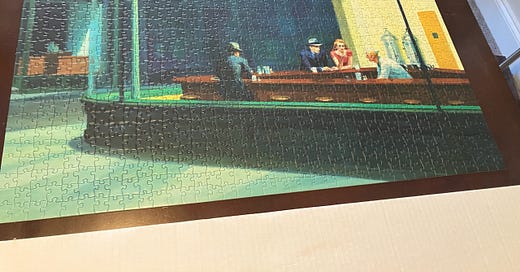

Here’s the puzzle I’m working on now:

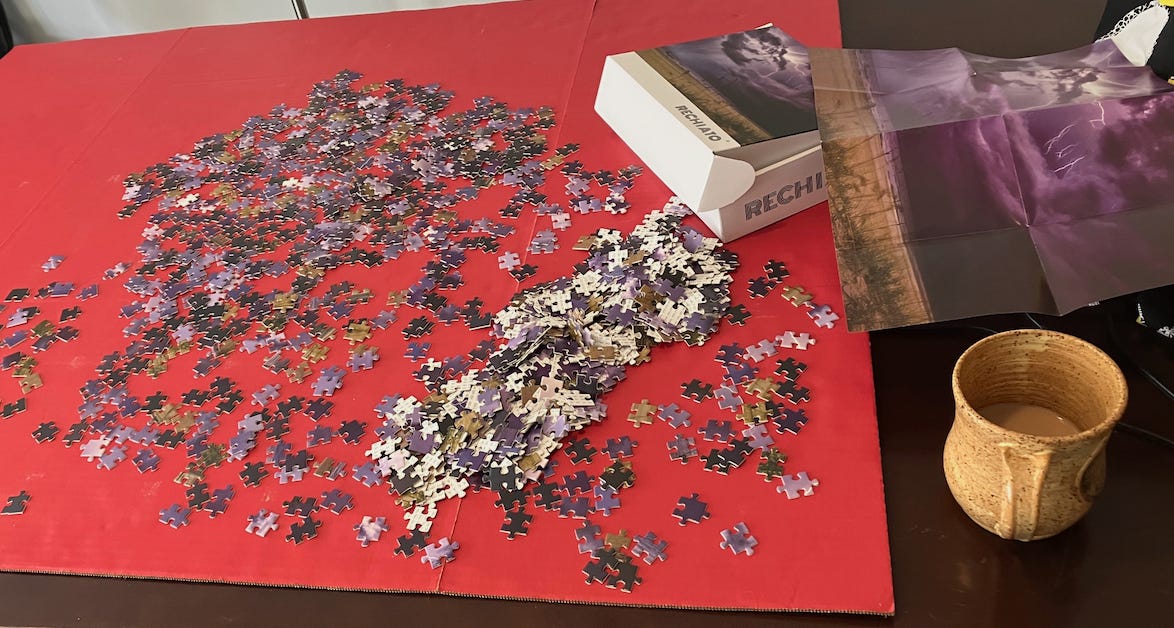

It started the way every novel / puzzle does: a total fucking mess.

I started by picking out the edge pieces, as one does. Start where it’s easiest, I tell my students (myself)—with a character or moment that feels solid, that you can already picture or hear in your mind. There’s no law that says writing has to be done The Hard Way.

I put together most of the puzzle’s outline fairly easily, but a dozen very similarly colored and shaped pieces prevented me from completing it. So I moved on. There’s no award for gritting your teeth and grunting through a very hard part of your writing. If something is truly flummoxing me on the page, I redirect toward a more approachable area of the text.

As I already mentioned, you don’t get extra points for doing things The Hard Way, so I headed over to the beach—a few rows of beige and brown pieces that felt delightfully approachable. On the page, I seek out quick wins—if I know what I want to do to a scene to make it better, I go for it.

The beach was approachable, though not without its challenges. When I got particularly stuck, I went back to the outline. Revisiting that problem with fresh eyes was very productive—each time I found a home for another one of those errant edges pieces.

I do this in writing all the time, hopping from page to page, filling in a little description here, drafting some more dialogue over there. Of course sometimes I’ll spend days motoring through a scene or series of scenes, but there’s no law that says you have to work in any kind of chronological or textual order. Work on whatever you want however you want!

Once the beach was done, I started picking out all the lightning pieces. Then I searched for patterns and similarities between them—that’s the “is the lightning skinny or fat?”, “is the sky around it dark or light?” bit.

This feels to me like scene building, which can be a bear. There’s a lot to manage. Each character (and there might be many) is doing at least these things:

1) saying things (or not saying them),

2) moving their bodies, gesturing, and/or making facial expressions,

3) existing in a location that has other objects and smells and sounds,

4) having feelings (or purposefully ignoring them).

I will argue that they are often also 5) thinking about totally unrelated stuff.

That’s a lot of pieces to fit together, so where to start? I approach scene building as I do a puzzle, finding two things I think fit together—Gertrude smelling the pie in the oven, Gertrude thinking about her grandmother—and seeing what happens when I put them next to each other.

I also know Gertrude is in a hurry. And that when she checks the pie, she feels the hot air against her face. I add these pieces to the other ones and see how it looks.

When they’re in an arrangement that seems reasonable, I fish for more pieces: Maybe somebody she lives with is hollering in the next room. Maybe they’re crying. Maybe they’re dead? I add, I rearrange, I see what clicks. Eventually, I have lightning.

*

And now, the elephant in the room: OUR WRITING DOESN’T COME IN A BOX WITH A PICTURE ON IT THAT SHOWS YOU YOUR FINAL DESTINATION. In writing we have to make the picture and the pieces ourselves.

Don’t forget your sandpaper and spackle, because after you make the pieces, you’re going to have to reshape them. You will make them bigger, then you will make them smaller. Then you will realize you made them too small and need to make them bigger again. Then you will realize you made them too big and you need to make them smaller. You will do this two or ten or three hundred times until finally your puzzle pieces are the right shape and size, fit together (almost) perfectly.

*

Now that I’ve constructed the beach and the lightning, it’s time to move onto the 750 pieces that are very similar shades of purple, gray, and black. It’s not going to be easy and it’s going to take a long time.

The puzzle that kicked off this obsession was Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks, purchased on a whim at the thrift store. Nighthawks posed a similar challenge—once the yellow background and four humans were accounted for, I was left with large swaths of nearly indistinguishable shades of black, dark blue, and dark green.

I ended up sorting the pieces by shape (a friend has a taxonomy of puzzle pieces; the pieces with a protrusion at the top and to the right are called “human pooping”). Over the course of several weeks, I pieced the blackness together. Sometimes it felt like pure trial and error, going all the way through the pile of pieces that might fit until I found the right one. Sometimes my instincts did the work, intuitively directing my fingers to the piece and its correct location.

The Nighthawk puzzle was acquired partly due to nostalgia; I lived in Chicago and used to admire the painting in person at the Art Institute. During those years, I was working on my first novel. Every day I went to the quiet room at the Lincoln-Belmont library and worked on my puzzle pieces. Some days it was exasperating. Other days I clicked a few pieces together and celebrated what felt like a great triumph. Anybody who has written a novel or some other long form product knows this painstaking process.

Sometimes, when I felt particularly unsteady, I would go to the Art Institute and visit with an artwork I considered my friend: a ~1,000 year old Buddha whose sturdy presence renewed my patience and faith. These, I know now, are the two most valuable traits in a writer.

Keep writing, friends.

Saving this one for future reference/the moments I know are coming of wishing I had a box lid picture to guide me through my novel draft. I remember working on seemingly impossible puzzles and wondering at the intense focus they require on one tiny piece of a picture: that green line intersecting with that blue dot: "Oh, I never expected the edge of a meadow to look like that." Novel writing also requires intense focus on one gesture. Sometimes I work on on one conversation for days...you solve that scene and move on to the next. Readers will whip by that page in a few minutes, never knowing the close focus I took to make that one bit a coherent part of the whole thing.

I'll definitely be revisiting this piece as I work through my own manuscript. So many gems here. This was one of my favorite reminders: "There’s no award for gritting your teeth and grunting through a very hard part of your writing. If something is truly flummoxing me on the page, I redirect toward a more approachable area of the text." Say it louder for the people in the back!